The history of Orthodoxy in 19th century Greece is extraordinarily complicated. Beginning with the Greek Revolution in 1821, the Church of Greece began to detach itself from the Ecumenical Patriarchate, declaring itself autocephalous in 1833 — a status that was not recognized by the Ecumenical Patriarchate until 1850. This newly-independent church dealt with many challenges, one of which was the emergence of unauthorized teachers. Some of these were Protestant missionaries who set up shop and tried to convert the country’s Orthodox faithful (which I’ll cover in the future). But other threats came from within. The two most prominent of these teachers were Theophilos Kairis and Apostolos Makrakis, both of whom were ultimately condemned by the Holy Synod of Greece. Today I’ll briefly review their stories.

Theophilos Kairis

Theophilos Kairis had been a leader in the Greek War of Independence and later set up a renowned school on the island of Andros, attracting students from all over Greece and beyond, including future bishops, political leaders, and professors. Kairis, who had been educated in the West, had imbibed the teachings of the Enlightenment and viewed Orthodox doctrine as backward. He openly rejected the doctrines of the Holy Trinity and the Incarnation of Christ, instead teaching that Christ was “a simple teacher of ethics among the Hebrews.” Kairis embraced Hellenism but rejected Orthodoxy, going so far as to give his students new, pagan Greek names to replace their Christian names. He accepted the existence of a transcendent God and the immortality of the human soul, and he constructed an entire philosophical-religious system – a new religion, basically – around his views, dubbing it “Theosebism” (“respect God”).

Kairis was a deceptive man; when asked by a student why he had become a priest despite clearly not believing in the teachings of the Church, he explained that he wanted the credibility of the priesthood among his fellow Greeks: “I believed that others have had similar compunctions concerning Christianity and they might not dare to open their heart to a clergyman of lower rank.”

Kairis’s open heresy led to his condemnation by the Greek Holy Synod in 1839 as “a denier of our blameless faith and a rebel against the Holy Church of Christ.” He was exiled to a monastery and later to Western Europe. The same year, Ecumenical Patriarch Gregory VI published his own encyclical against Kairis and his teachings. Eventually, the unrepentant Kairis was excommunicated. Because of his support for Kairis, Fr Theoklitos Pharmakides, secretary of the Holy Synod of Greece, was ousted from his position.

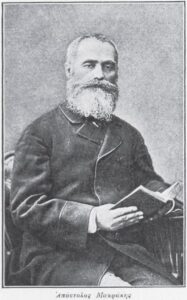

Apostolos Makrakis

Four decades later, on December 18, 1878, the Holy Synod of Greece condemned the popular religious intellectual Apostolos Makrakis as a heretic. Makrakis was kind of the opposite of Kairis: he was the leader of an “awakening movement” in Greece, preaching against the Enlightenment and the entrenched church and state structures in the country. He’s been described as an “omnivorous polymath” who taught himself many languages and wrote long Biblical commentaries. More than just speaking out, Makrakis had formed actual organizations to push for reform, including a private school set up to compete with the University of Athens and, eventually, his own Protestant-style church. Makrakis’s condemnation by the Holy Synod was based on his anthropological teachings – he espoused the idea that humans are composed of “carnal,” “psychic,” and “spiritual” bodies, and that the goal of human life is to evolve from the physical body to the spiritual body. The Holy Synod viewed this as basically a gnostic way of thinking, a callback to Platonic and Manichean ideas from long ago, incompatible with the Orthodox understanding of the human person.

After Makrakis was condemned by the Holy Synod, the Greek government shut down his church and school, and he was sentenced to two years in prison for heresy. Only forty-seven years old when he was declared a heretic, Makrakis lived well into his seventies, dying in obscurity in 1905.

Main Sources

On Theophilos Kairis:

Charles A. Frazee, The Orthodox Church and Independent Greece 1821-1852 (Cambridge University Press, 1969), 147-150.

E. Theodossiou, Th. Grammenos, and V.N. Manimanis, “Theophilos Kairis: The Creator and Initiator of Theosebism in Greece,” The European Legacy 9:6 (2004), 783-797. (This is the most comprehensive source I’ve found on Kairis; however, it takes a very pro-Kairis position.)

Vrasidas Karalis, “Greek Christianity after 1453” in Ken Parry, ed., The Blackwell Companion to Eastern Christianity (Blackwell Publishing, 2007), 169-170.

On Apostolos Makrakis:

Vrasidas Karalis, “Greek Christianity after 1453” in Ken Parry, ed., The Blackwell Companion to Eastern Christianity (Blackwell Publishing, 2007), 172.

Amaryllis Logotheti, “The Brotherhood of Theologians Zoe and Its Influence on Twentieth-Century Greece” in Aleksandra Djuric Milovanovic and Radmila Radic, eds., Orthodox Christian Renewal Movements in Eastern Europe (Palgrave Macmillan, 2017), 287-288.

Ioannis Zelepos, “Amateurs as Nation-Builders? On the Significance of Associations for the Formation and Nationalization of Greek Society in the Nineteenth Century” in Hannes Grandits, Nathalie Clayer, and Robert Pichler, eds., Conflicting Loyalties in the Balkans: The Great Powers, the Ottoman Empire and Nation-Building (I.B. Tauris & Co., 2011), 70.

There’s also a lot about Makrakis at a pro-Makrakis website, www.apostolosmakrakis.com.

Leave a Reply