In 1054, Pope Leo IX of Rome wrote a letter to Ecumenical Patriarch Michael Cerularius, defending his claims to supremacy by citing a document known as the “Donation of Constantine.” This document purported to be a decree of St Constantine the Great, endowing the Pope of Rome with temporal imperial powers over the western part of the Roman Empire. The decree presents the evocative image of the Roman Emperor serving the Pope: “holding the bridle of his horse, out of reverence for St. Peter, we performed for him the duty of groom.” Most critically, the Donation grants to the Papacy “supremacy as well over the four principal sees: Alexandria, Antioch, Jerusalem, and Constantinople, as also over all the churches of God over the whole earth. And he who for the time being shall be pontiff of that holy Roman Church shall be more exalted than, and chief over, all the priests of the whole world and, according to his judgment, everything which is to be provided for the service of God or the stability of the faith of the Christians is to be administered.”

If you know a little bit about church history, you can probably spot some immediate problems with this text. It assumes the existence of the “Pentarchy” of chief sees (Rome, Constantinople, Alexandria, Antioch, and Jerusalem), but this wasn’t yet fully formed in St Constantine’s day. It wasn’t until the Second Ecumenical Council, decades after Constantine’s death, that Constantinople was raised to a preeminent position, and Jerusalem’s elevation came even later.

The reason is simple: the “Donation of Constantine” was a fake. It’s been dated by scholars to the late first millennium — created, possibly, as part of the jockeying for power between the papacy and the Frankish rulers in the mid-eighth century. Later, in the eleventh century, the Papacy tried to use the Donation as part of its push for supremacy over the Patriarchate of Constantinople.

Counterintuitively, the Constantinopolitans didn’t just reject the Donation outright. On the contrary, in the twelfth century, the most influential of all the Byzantine canonists, Theodore Balsamon, incorporated the Donation into his own work, using it to elevate the claims of the Ecumenical Patriarchate. Balsamon’s logic was that, if Old Rome was given loads of privileges by St Constantine, those privileges naturally now belong to New Rome. According to Dimiter Angelov in his paper “The Donation of Constantine and the Church in Late Byzantium,” “Balsamon explicitly states that [Michael] Keroularios [patriarch in 1054] and ‘other patriarchs’ used the Donation of Constantine to legitimize their political ambitions. Keroularios’s political ambitions encroached on imperial prerogative. According to eleventh-century Byzantine historians, Keroularios put on purple imperial buskins, assumed the role of powerful political mediator by arranging for the accession of Isaac I Komnenos (1057–59) on the imperial throne, and asserted the authority of the patriarchal office in managing the wealth of the church.”

By the fifteenth century, the document had been conclusively proven to be a forgery. It had nothing at all to do with St Constantine and represents an anachronistic attempt to project late first millennium papal claims back onto the fourth century.

***

It is usually thought that the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople was the chief of all the Orthodox faithful of the Ottoman Empire. These peoples were organized — as were other non-Muslim subjects of the sultan (Armenians, Jews, etc.) — in their own religious communities, that is, in their respective millets, a Turkish term that actually means “people” or “nation.” The Ecumenical Patriarch was a milletbasi, that is, the head of the Orthodox millet called in Ottoman Rum milleti or millet-i Rum. The Ottomans used the term Rum (“Romans”) to identify all the Orthodox, Greeks and non-Greeks, of the empire. The patriarch of Constantinople was responsible to the Ottoman administration for all matters concerning the Orthodox religious community. This last point drove Greek scholars of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries to name the patriarch Ethnarches, that is, “nation-leader.” Influenced by the nationalist ideals of the time, they identified the Greek nation with the “Roman” (Orthodox) religious community.

– Professor Paraskevas Konortas, University of Athens

***

Immediately after the Ottoman conquest of Constantinople in 1453 — so the story goes — Sultan Mehmet II set about organizing all of the Orthodox Christians of his empire into a “millet” — that is, a “people” or “nation” — led by the Ecumenical Patriarch. In his classic work The Great Church in Captivity, Steven Runciman presents this as a very intentional project of Mehmet. “If the Greek milet was to be organized, the first task was to provide it with a head.” Mehmet chose the scholar-monk Gennadius Scholarios, “and together they worked out the terms for the constitution to be granted to the Orthodox.” After his ordination as Patriarch, Gennadios “mounted on a magnificent horse which the Sultan had presented to him [and] rode in procession round the city…”

Runciman describes the new role of the Ecumenical Patriarch as being “the Ethnarch, the ruler of the milet.” He goes on, “The Patriarch as head of the Orthodox milet was to some extent the heir of the Emperor.” He had numerous new powers as a civil, not just religious, authority — and those powers extended over the whole of the Orthodox community, not just the territories under the ecclesiastical control of the Ecumenical Patriarchate. “Further powers were added when the Ottoman Empire expanded southwards,” Runciman explains. “In the course of the sixteenth century the Sultan acquired dominion over Syria and Egypt, thus absorbing the lands of the Orthodox Patriarchates of Alexandria, Antioch and Jerusalem. The Sublime Porte wished to centralize everything at Constantinople; and the Great Church followed its lead. As a result the Eastern Patriarchates were put into a position of inferiority in comparison with that of Constantinople.”

I’ve always accepted this story as being obviously true: for better or worse, all of the Orthodox in the Ottoman Empire were, from 1453-54 on, organized into a single “Rum millet” and subject to the civil authority of the Ecumenical Patriarchate. And while the other Patriarchates retained ecclesiastical independence in theory, they were, for all intents and purposes, mere appendages of Constantinople.

But the story isn’t true.

***

In 1982, a young scholar named Benjamin Braude published a landmark study, “Foundation Myths of the Millet System,” arguing that the whole idea of the millet system, as presented by Runciman and so many others, is an anachronism – a projection of a much later Ottoman reality backward onto earlier periods of history, when in fact it simply did not exist in those previous centuries. At the time of Mehmet’s conquest, “millet” was a more generic term for “people”; Braude shows that it was originally used to refer to the Muslim people, and it later came to be applied to the Christian people more generally. For example, Braude points out that Sultans in the sixteenth century, in correspondence with the monarchs of England, France, and Venice, would refer to them as members of “the Christian millet” by this obviously not meaning that they were Orthodox Christian subjects of the Ottoman Empire.

Braude notes that there’s a curious silence in the contemporary Greek chronicles of this era, regarding the relationship between Mehmet and the Orthodox Church. “Only one describes the appointment of Gennadios to the Patriarchate. The authentic Sphrantzes says nothing; Laonikos Chalkokandyles says nothing; and Doukas says nothing. Each does discuss Constantinople after the Capture so the silence on Mehmed and the Patriarchate is bizarre.” One writer does talk about this subject: Kritovoulos, a Greek serving in Mehmet’s court. Here is what Kritovoulos has to say:

“In the end, he made him Patriarch and High Priest of the Christians, and gave him among many other rights and privileges the rule of the church and all its power and authority, no less than that enjoyed previously under the emperors. He also granted him the privilege of delivering before him fearlessly and freely many good disquisitions concerning the Christian faith and doctrine. And he himself went to his residence, taking with him the dignitaries and wise men of his court, and thus paid him great honor. And in many other ways he delighted the man.

“Thus the Sultan showed that he knew how to respect the true worth of any man, not only of military men but of every class, kings, and tyrants, and emperors. Furthermore, the Sultan gave back the church to the Christians, by the will of God, together with a large portion of its properties.”

So Gennadios was invested with the office of the patriarchate – but, as historian Tom Papademetriou notes, “this raises the question of what ‘rights, and privileges,’ ‘rule of the church,’ ‘power and authority’ really mean.” There’s no contemporaneous evidence that Gennadios was made the head of all Orthodox Christians in the Empire, or anything like that. Patriarch Gennadios himself, whose writings are extant, apparently never wrote anything that could shed more light on this subject, either.

***

One of the many scholars who carried forward Braude’s work was Professor Paraskevas Konortas, who, in 1999, published a remarkable paper, “From Ta’ife to Millet: Ottoman Terms for the Ottoman Greek Orthodox Community.” Konortas examines Ottoman ecclesiastical documents and finds that the term “millet” was first used to refer to non-Muslim religious communities within the Empire in the seventeenth century and didn’t become prevalent until the nineteenth century — hundreds of years after the supposed creation of the “Rum millet.”

But if the Ottomans weren’t using “millet,” what term did they use? Konortas finds that, “during the first period of Ottoman rule, we find the term ‘ta’ife’… which in Ottoman Turkish generally means ‘group.’” This term — ta’ife — was used to refer to groups in general, including guilds. There were not just one but many Orthodox teva’if (groups) in the Empire. According to Konortas, this is attributable to three factors:

- Prior to the fall of Constantinople in 1453, the Ecumenical Patriarch was not under the sultan’s authority. During this period, each metropolitan or bishop in the sultan’s dominions was the chief of a separate Orthodox group (ta’ife).

- The Ottoman administration was unfamiliar with the Orthodox ecclesiastical tradition.

- In the sixteenth century, the Ottoman authorities preferred to keep their Orthodox subjects divided, as a way to more effectively control them.

Konortas writes, “One thing seems certain: During the three centuries that followed 1453, according to ecclesiastical berats or fermans, the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople was defined neither as ethnarches nor as milletbasi.”

So when did the Orthodox shift from being divided into multiple teva’if (groups) to a single ta’ife? Based on the documentary evidence, Konortas concludes that, by the last quarter of the sixteenth century, the Ottoman administration was already recognizing a single Orthodox ta’ife. The term “millet” (nation), on the other hand, “does not seem to have prevailed before the nineteenth century.” This was the Tanzimat era, which “paved the way for the triumph of nationalism in the empire.” Konortas asserts, “Only from this moment on can one speak of a ‘patriarch-head of a religious community’ or even a ‘(Patriarch)-leader of the (Greek) nation.”

***

So much for the term “millet.” What about the designation “Rum” (Romans) to refer to the Orthodox? Konortas writes, “Conventional theory, based on the conditions of the nineteenth century, claims that… already in the fifteenth century the Orthodox community was known as Rum milleti.” But the conventional theory is wrong: in the official Ottoman ecclesiastical berats and firmans, “Rum” does not mean Orthodox until the end of the eighteenth century.

Incidentally, this helps explain why Mehmet II would take the title “Kayser-i Rum.” He was certainly not claiming to be “Emperor of the Orthodox”; by taking that title, he was purporting to be the Roman Emperor, identifying his empire as Roman. (For more on this, see F. Asli Ergul’s 2012 paper “The Ottoman Identity: Turkish, Muslim or Rum?”)

In fifteenth century Ottoman documents, the Orthodox are called “Nasrani” — that is, “Nazarenes.” In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, this term was replaced by “kefere,” which means “infidels.” Konortas explains, “It seems that the Orthodox were called ‘infidels’ because they were the most numerous non-Muslims (i.e., infidels) of the empire.” The shift from kefere to “Rum” took place in the eighteenth century, and Konortas explains it by three factors:

- The progressive influence of the Greek element (“Phanariots”) in the Orthodox Church as well as the Ottoman court;

- The gradual decline of the Ottoman central administration, which created an opening for Orthodox hierarchs to acquire more privileges; and

- The infiltration of nationalist ideas in the empire.

***

In 1525, official Ottoman documents refer to the Ecumenical Patriarch as “Patriarch of the groups of the infidels.”

In 1544: “the actual patriarch of the well-guarded Istanbul and of the countries and areas that depend on it.”

In 1574: “the actual patriarch of the infidels who reside in Istanbul the ‘well-guarded.’”

In the seventeenth century: “the actual patriarch of the infidels of Istanbul and of its dependencies.”

From 1700-1750: “the ‘Roman’ patriarch of Istanbul and its dependencies.”

From 1750 to the nineteenth century: “the patriarch of the ‘Romans’ of Istanbul and its dependencies, the example of the heads of the Christian community.”

Observing these changes, Konortas writes, “The difference between the conditions of the sixteenth century and those of the nineteenth century is dramatic. After 1750, the title of the Ecumenical Patriarch brings to mind the titles granted by the sultan to the highest dignitaries of the empire.” Konortas also notes that the “dependencies” referred to in these documents “coincide with the territorial jurisdiction of the Ecumenical Patriarchate, as it is described by ecclesiastical sources.” That is, the Ecumenical Patriarch appears to be the civil head only of the Orthodox who are under his ecclesiastical jurisdiction.

“During the three centuries that followed 1453, the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople seems to be neither head of a nation nor head of a religious community,” Konortas writes. “In other words, he exercised his authority over only a part of the Orthodox community of the Ottoman Empire who is not yet defined as ‘Romans.’”

***

So what changed? According to Konortas, “The powers of the patriarch of Constantinople seem to have been progressively extended over the whole Orthodox community of the empire in two ways: de jure and de facto.”

Firstly — de jure — “the Ecumenical Patriarch succeeded in obtaining Ottoman documents issued in 1766 and 1767 allowing the abolition of the autocephalous archbishoprics of Archis [Ohrid] and Ipekion [Pec].” These two autocephalous Churches basically correspond to the modern-day patriarchates of Bulgaria and Serbia (and also, in the case of Ohrid, the “Macedonian Orthodox Church,” about whose name there’s a lot of dispute in Greek and Bulgarian circles).

Secondly — de facto — the Ecumenical Patriarch “began to interfere in the internal affairs of the three other Orthodox patriarchs residing in the empire, as well as the autocephalous archbishoprics of Cyprus and Sinai. This was primarily due to the fact that the Ecumenical Patriarch was seated in Constantinople, where the sultan also resided…”

Konortas concludes: “we can confidently claim that the patriarch of Constantinople (backed by the very powerful Phanariot aristocracy) succeeded in having the Orthodox community of the empire be defined by the Ottomans as Rum milleti and was able to exercise fully his authority over the whole Orthodox community of the empire only in the eighteenth century.”

Thus it was not Mehmet II and Patriarch Gennadius in 1453 who set up the Rum millet system with the Ecumenical Patriarch at its head; rather, says historian Hasan Çolak in his book The Orthodox Church as an Ottoman Institution, “The millet system is a nineteenth-century construct, which has been projected back on to the earlier periods of Ottoman rule.”

***

Where did this misconception — the myth of Mehmet’s “donation” to Gennadius — originate? According to Tom Papademetriou in his fantastic 2015 book Render Unto the Sultan: Power, Authority, and the Greek Orthodox Church in the early Ottoman Centuries, the story begins with an Armenian Ottoman writer named Ignatius Moradgea d’Ohsson, who published a history of the Ottoman Empire in 1824. In describing the Orthodox Church, d’Ohsson basically looked at the state of affairs in his own day and projected it backward onto the entire history of the Ottoman Empire. His primary source was a 1789 investiture berat issued by the Sultan to Ecumenical Patriarch Neophytos VII, which granted the Patriarch broad civil and religious authority. But as Papademetriou notes, “This 1789 document is valuable to describe the status of the patriarch only in a late eighteenth-century Ottoman social milieu. D’Ohsson, and historians who came after him, however, assumed that the document’s form had not changed substantially over time. The assumption was that based on this legal document, Ottoman legal practice toward the Church could be projected backwards in time to cover all periods of Ottoman rule. As a result, the imprecise use of this document has distorted subsequent presentations by historians discussing non-Muslim communities in the Ottoman Empire.”

Those misled historians include the great Sir Steven Runciman, who unwittingly relied on the 1789 berat by way of the twentieth century historian Theodore Papadopoullos, who in turn relied on d’Ohsson. Runciman’s inadvertent error unfortunately taints his otherwise wonderful The Great Church in Captivity.

A major byproduct of this anachronistic misunderstanding is that twentieth century writers began to propound the myth that the other Eastern Patriarchates became mere dependencies of the Ecumenical Patriarchate. For example, Philip Sherrard, in his respected book Greek East and Latin West, wrote “the Patriarch of Constantinople was now regarded as the head of the local churches, in whose hands was concentrated all temporal and juridical power. The other Patriarchs, those of Alexandria, Antioch, and Jerusalem, although theoretically independent, were in fact reduced to a position of inferiority in relation to the Oecumenical Patriarch, since the latter was the sole intermediary through whom they could communicate with the Porte, and it was he alone who could apply for the berats of their nomination.” It’s true that Constantinople began to have an outsized influence vis-a-vis the other patriarchates by the latter stages of the Ottoman Empire, but that was not the case in earlier centuries, and certainly does not date back to Mehmet II.

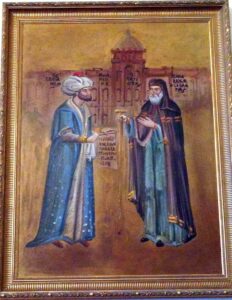

It’s not just a non-Orthodox historian like d’Ohsson who contributed to this misreading of history, though. In the latter half of the nineteenth century, the Ecumenical Patriarchate was in a constant state of defensiveness, as the Ottoman government continually eroded the Patriarchate’s privileges in the Empire. In June 1880, as he struggled with the latest attack on the Phanar’s privileges, Patriarch Joachim III corresponded with his spiritual son, the (Greek Orthodox) ambassador of the Ottoman Empire in London. The ambassador sent Joachim a picture he had found in a book, depicting Mehmet the Conqueror and Patriarch Gennadios Scholarios. Joachim asked the ambassador to obtain a copy of this picture as an oil painting. The resulting image, which shows Mehmet handing Gennadios a document symbolizing the privileges of the Patriarchate, would be hung in the Great School of the Nation (constructed in 1882). This sent a clear visual message from Joachim to the Ottomans and everyone else that the privileges of the Patriarchate in the Empire were inalienable, bestowed as they were by the great Mehmet the Conqueror himself.

In the mid-1980s — just a few years after Benjamin Braude debunked the early origins of the millet system — a new residence for the Ecumenical Patriarch was completed at the Phanar. Three new mosaics were installed, one of them is directly based on Patriarch Joachim’s painting. The mosaics are described in Render unto the Sultan (and the Mehmet-Gennadios mosaic is shown at the top of the present article):

“On the east entry wall of the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople in Istanbul is a modern mosaic featuring the Ottoman Sultan Mehmet II, conqueror of Constantinople, and the Patriarch Gennadios Scholarios, the first patriarch invested following the conquest of the city in 1453. The image shows Sultan Mehmet II offering a document promising Patriarch Gennadios all the privileges of preceding patriarchs. For the patriarchate and historians alike, this moment captured in stone represents the establishment of the millet system, a system wherein the Church governed as a state within a state, with the patriarch serving as the communal leader (millet başı) or ethnarch. The millet system became the dominant paradigm employed to describe non-Muslims under Ottomans rule. This powerful mosaic, and its counterpart on the opposite wall depicting the Apostle Andrew and his disciple Stachys, the first bishop of ancient Byzantion, was commissioned in the late 1980s. They dramatically remind those who enter that the Patriarchate of Constantinople possesses ancient authority and prerogatives from Apostolic times, authority that was confirmed by none other than the conquering Sultan Mehmet II. The mosaic announces the patriarchate’s authority as the legitimate leader of the Greek millet of the Ottoman Empire. The implication is that this authority must continue uncontested to the present.”

***

The work of scholars like Benjamin Braude and those who followed him, such as Papademetriou and Konortas, has conclusively demonstrated that our reading of “Rum” and the “millet system” all the way back to the Ottoman conquest of Constantinople is an anachronism — perhaps an understandable one, but an anachronism nonetheless. In reality, these concepts originate in the eighteenth century — almost the same historical moment when nationalism emerged.

The Mehmet-Gennadios narrative, then, is basically a modern equivalent to the Donation of Constantine. Both purported to tell the story of an era some four centuries earlier, and both emerged in the context of contemporary struggles for power between the civil authorities and church leaders. Both made the same error of anachronistic back-projection of present realities (or desires) onto the distant past. Both even featured gestures of respect from an emperor to a bishop, prominently involving a horse!

The biggest difference between the two myths, as I see it, is that the Donation of Constantine was an act of intentional deception while the “Donation of Mehmet” was more of an unintentional misunderstanding of history. But neither story is actually true.

Leave a Reply