In all but one of the world’s Orthodox Churches today, after a fast-free Bright Week, the Wednesday and Friday fasts resume. This happens even though we continue to exclaim “Christ is risen!” until Ascension, and we don’t kneel until Pentecost. The bizarre result of this is that the non-fasting period after Christmas is actually longer than the non-fasting period after Pascha — and while, after Christmas, we don’t resume fasting until the eve of Theophany, with Pascha, we fast many weeks before the eve of Ascension. But there’s one exception to this practice: the Antiochians, who don’t fast at all until after Ascension. Where did this Antiochian exception come from?

According to a page on the Patriarchate of Antioch’s website, “a decree was issued at the Orthodox Patriarchate of Antioch during the Lebanese civil war by his Beatitude Ignatius Hazim to eliminate the fasting period between Pascha and Pentecost.” The Lebanese Civil War lasted from 1975 to 1990, and Ignatius became patriarch in 1979, so this must have happened between 1979 and 1990. I haven’t been able to find any details about this patriarchal decree. But then, in May of 1997 — with Ignatius still patriarch — the Holy Synod of Antioch made this a patriarchate-wide practice, albeit with the fast-free period ending at Ascension rather than Pentecost. Here’s an excerpt of the decision, published by the Antiochian Archdiocese of North America in its Word Magazine, September 1997:

The Holy Synod decided that the Orthodox faithful do not have to fast between Pascha (Easter) and Ascension. The Paschal time is a joyful time and all Divine Services should reflect this reality, i.e., the funeral service, and the rest of the liturgical services should follow the pattern of the services during The New Week (Bright Week).

Were the Antiochians innovating by abolishing the Wednesday and Friday fasts during the Paschal season? Not exactly. I have heard — but have yet to see specific evidence for this — that there are precedents for this in the Orthodox East.

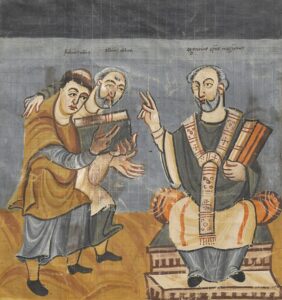

Also, it turns out that there’s precent in the pre-schism Orthodox West. I’m not aware of any full studies on the topic, and there’s no evidence that the Antiochian synod has any of this on their minds in 1997, but recently on X, Scriptorium Press posted the following excerpt from the 9th century Frankish Benedictine (and Orthodox) monk Rabanus Maurus in his On the Formation of Clergy 2:21. Rabanus Maurus’s main focus here is on the Apostles’ Fast, but he also explains the Orthodox practice of not fasting until after Pentecost.

The second fast is that which according to the canons begins on another day after Pentecost, following what Moses said: ‘From the beginning of the barley month you will count off seven weeks’ (cf. Deut 16.9). On the authority of the Gospel, this fast is completed after the Ascension of the Lord by many who hold as historical that witness of the Lord, where He says: ‘Can the children of the bridegroom mourn as long as the bridegroom is with them? But the days will come when the bridegroom will be taken away from them, and then they will fast’ (Mt 9.15).

For they say that for those forty days after the Lord’s Resurrection, during which it is later read He kept company with the disciples, it is not required either to fast or to grieve, because we are joyful. Indeed, after that time is completed in which Christ hastening to the heavens withdrew from the tangible present, then a fast ought to be declared so that through humility of heart and abstinence from meat we might merit to receive the Holy Spirit promised from heaven.

But just as we said, rightly and by way of a general rule, it was established by the fathers that this begin after Pentecost, so that in the joy of the promised Holy Spirit we await His coming exulting in the praises of God, and then, renewed through His grace and inflamed with spiritual zeal, we devote effort to fasting and abstinence. The words of Luke agree on this matter in which he recounted that the Lord, who was about to ascend to the heavens, instructed His disciples: ‘But you,’ He said, ‘stay in the city until you are clothed in power from on high’ (Lk 24.49). But if anyone of the monks or clerics desires to fast, they are not to be prohibited, because it is read that both Anthony and Paul and other ancient fathers in those days in the desert abstained and did not relax abstinence, except only on the Lord’s day.

Even earlier — and still in the West — St Ambrose of Milan (4th c.) said this in “Sermon 61” (the full text of which I haven’t found, but it’s quoted by John Sanidopoulos in a 2013 article):

“The Lord so ordained it,” says St. Ambrose (†397), “that as we have participated in his sufferings during the Forty Days, so we should also rejoice in his Resurrection during the season of Pentecost. We do not fast during the season of Pentecost, since our Lord Himself was present amongst us during those days … Christ’s presence was like nourishing food for the Christians. So too, during Pentecost, we feed on the Lord who is present among us. On the days following his ascension into heaven, however, we again fast” (Sermon 61).

Thus, while the Antiochian practice is very recent, it has significant precedent in church history. It’s also notable that, in every instance, the rationale given for non-fasting is the same.

If anyone knows of other examples of this practice in church history, please let me know!

Leave a Reply